Cautionary Tale: Unexpected inventor of a dependent claim

A cautionary tale where an inventor is unexpectedly discovered causing ownership grief for the applicant of an Australian patent application. The tale shows how the smart use of divisional applications can help turn a cautionary tale into a strategic win.

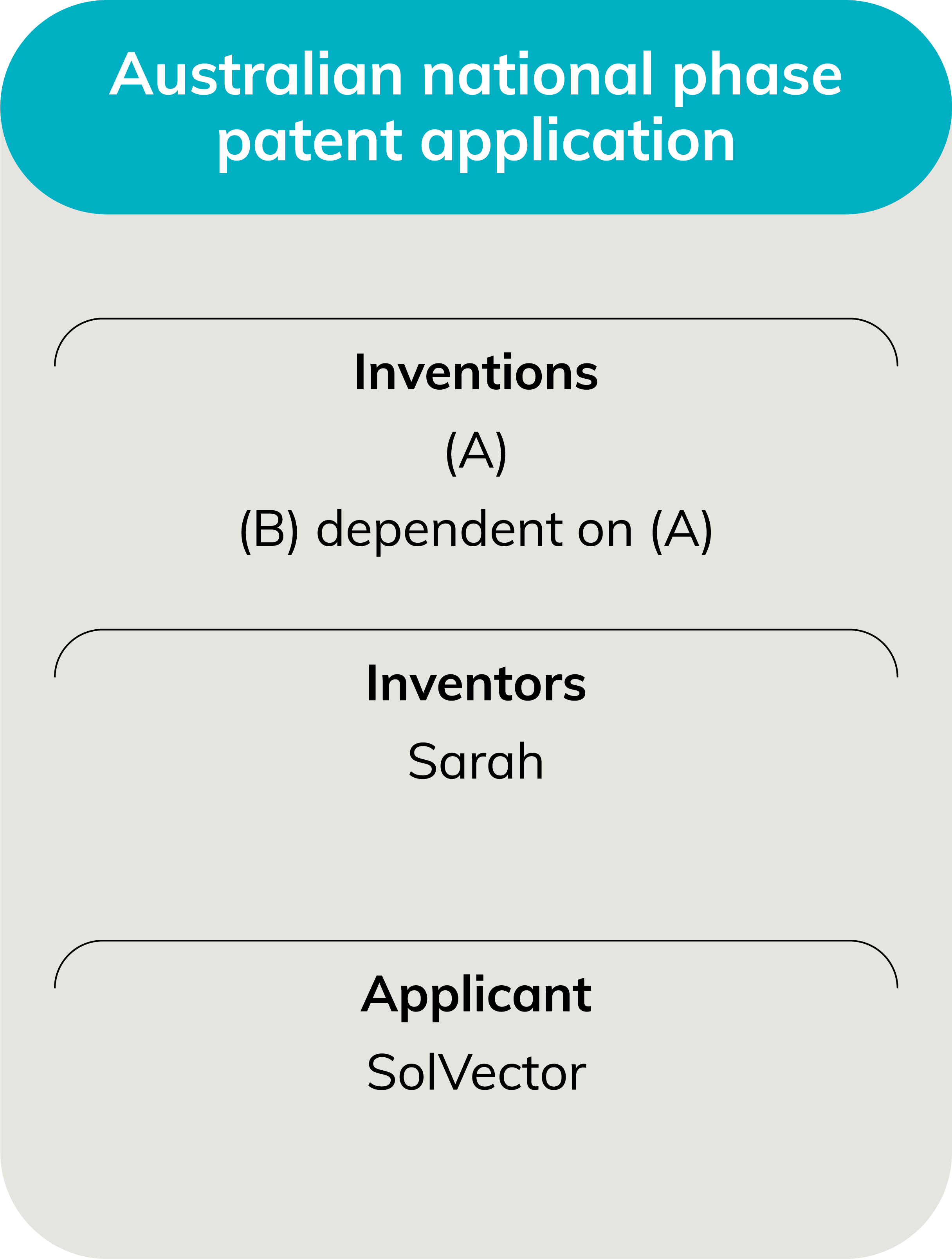

Australian national phase application filed

This cautionary tale starts in late 2020, when SolVector Pty Ltd (SolVector), an Australian renewable energy startup, filed an international (PCT) application for a novel solar panel tracking system. The specification described:

- (A) A lightweight motor system governed by a solar exposure algorithm (subject of Claim 1), and

- (B) A failsafe locking mechanism to prevent mechanical failure of (A) the motor system during high winds (subject of Claim 3 dependent on Claim 1).

It was agreed by all that Dr Sarah Kwon was the only inventor. In-house counsel at SolVector checked Sarah’s employment contract and confirmed that all IP passed to SolVector. Congratulations all round, a thorough job done!

The PCT application was filed with SolVector as the sole applicant. Then in 2022, the PCT application entered national phase in Australia, again with SolVector as the sole applicant.

Entitlement challenged

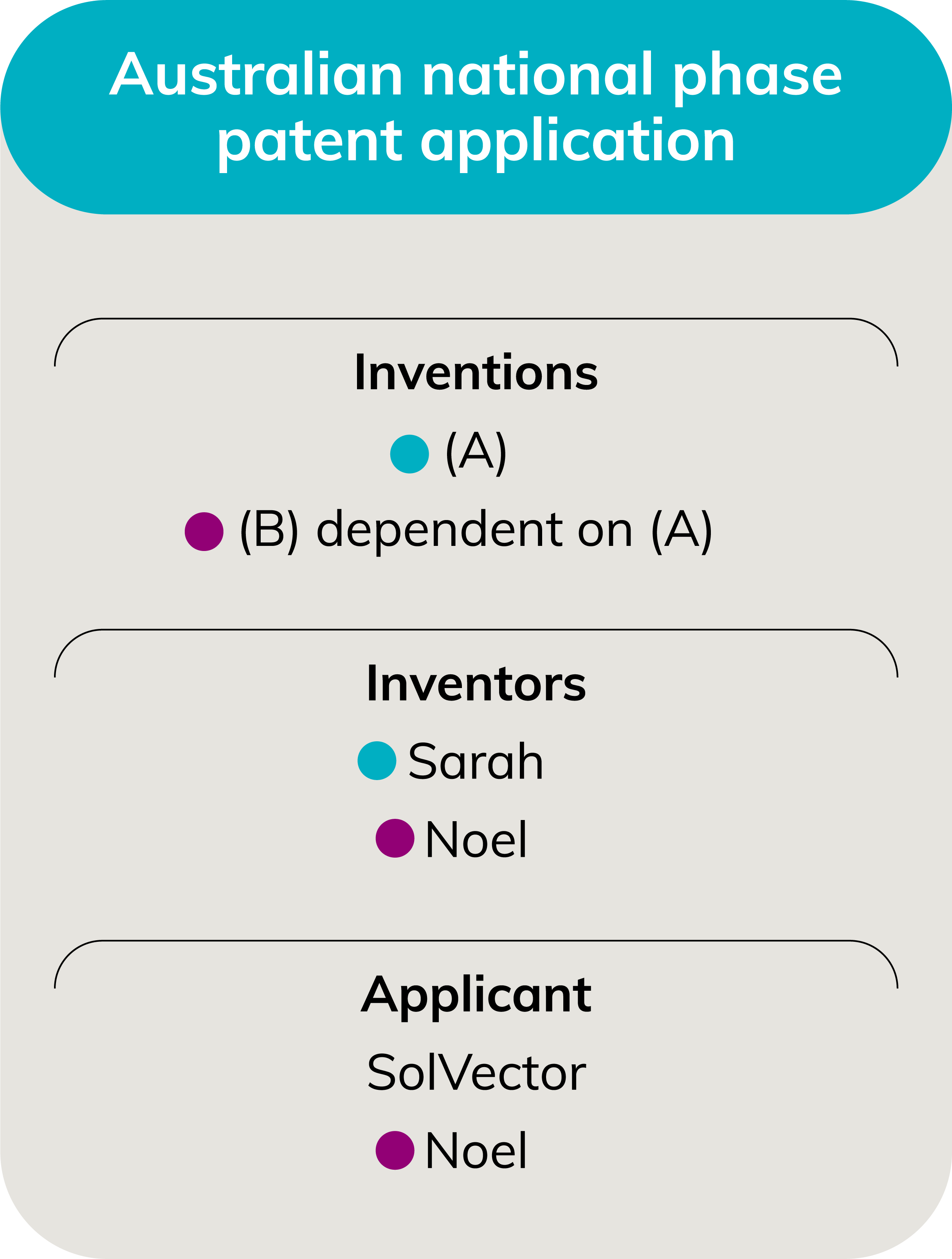

Now the trouble begins! Before acceptance of this Australian patent application, SolVector received a notice from IP Australia under section 36.1 A request for a determination of entitlement had been filed by Noel King. It turns out that Noel was a contractor of SolVector who had worked briefly on the prototype, but in-house counsel at SolVector was never told this. Noel alleges in his request that he was the true inventor of dependent Claim 3, which related to (B) the locking mechanism.

Noel submitted a statutory declaration along with annotated CAD drawings and Slack messages which he claimed proved that (B) the locking mechanism was also his idea.

Noel’s request appeared straightforward. If he was an inventor of Claim 3, then SolVector’s claim to full ownership was not correct. Noel wanted to be listed as an inventor, and in turn a co-owner of the Australian patent application.

In-house counsel at SolVector determined that unfortunately Noel’s contractor agreement with SolVector provided that all IP that Noel created remained with Noel. Clearly that would never have happened had they known about the agreement, but of course they didn’t. Since no one picked this up at the time, Noel had not signed a separate IP agreement either.

Finding a solution

SolVector’s leadership initially downplayed the challenge. "It’s a dependent claim" they argued. "He didn’t invent the core tracking system. Claim 3 wouldn’t exist without Claim 1." Quite annoyed SolVector’s leadership suggested that they simply delete Claim 3 from the specification and be done with it.

Good solution?

No, it’s not a great solution. We know from Polwood Pty Ltd v Foxworth Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 9, that in Australia claims are not solely determinative of the “invention” against which inventorship is assessed, which is unlike other jurisdictions, such as the United States of America (see this article on this topic). Rather, the invention or inventive concept of a patent or patent application is discerned from the whole specification. A contribution to a dependent claim can still qualify someone as an inventor, provided that the dependent claim embodies a distinct inventive concept to which the person contributed.

“Ok” said SolVector’s leadership, “let’s delete the description of (B) the locking mechanism as well as Claim 3”.

Problem solved? It’s an improved solution. But here’s an even better one:

Step 1

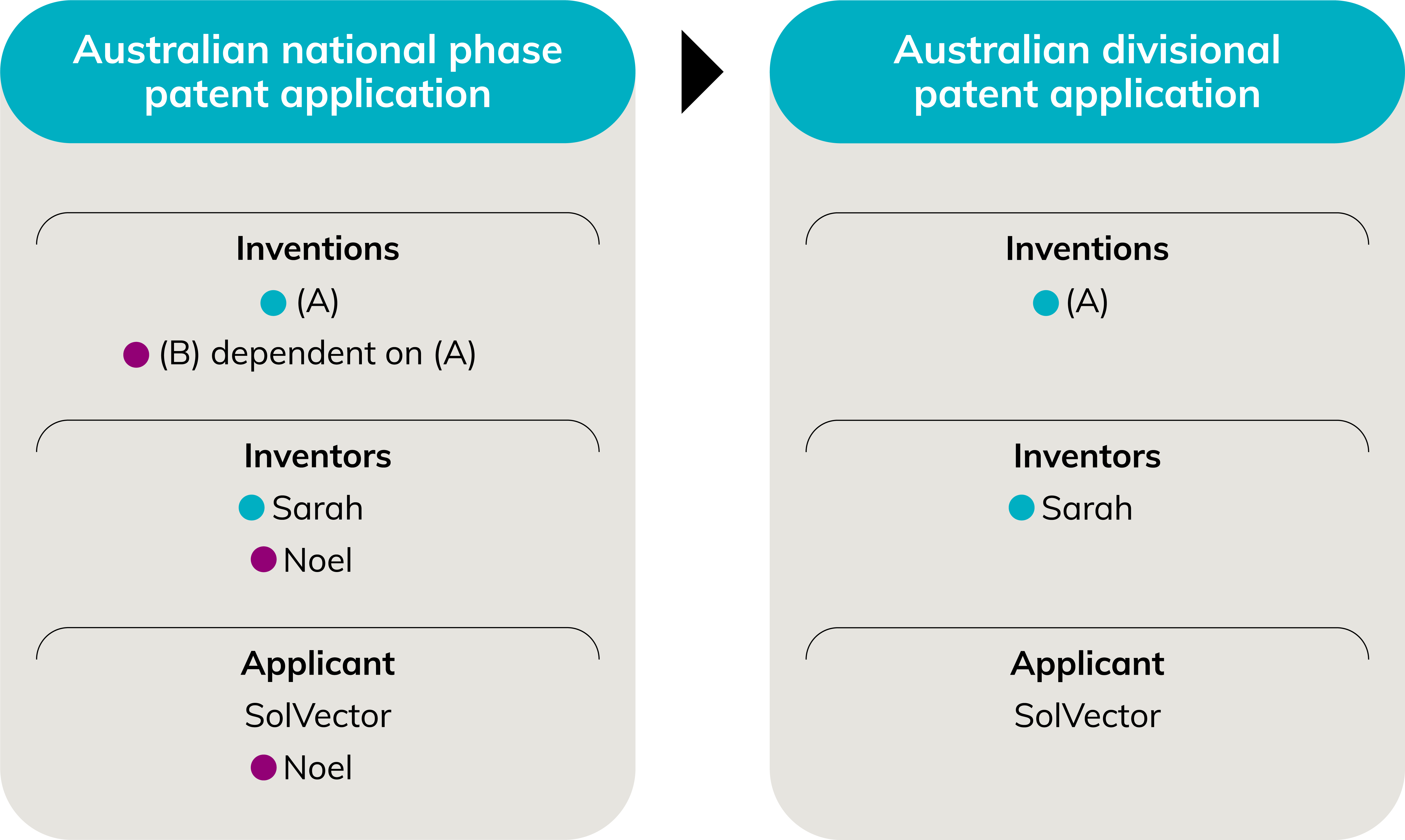

File a divisional application which does not include Claim 3 and does not include the related contested matter (B) the locking mechanism in the divisional specification. This involves:

- Removing Claim 3

- Deleting all description in the specification that relates to (B). Careful attention is needed when doing this to ensure that sufficient information remains in the specification to satisfy the requirements for disclosing the best mode, and that sufficiency is still satisfied for the remaining claims. Keep in mind it is possible to add information to satisfy these requirements in a divisional application in Australia without changing the priority date. The result must be that the divisional specification is silent on (B) the locking mechanism. This was possible in this case because of the distinct nature of the inventions (A) the motor system and (B) the locking mechanism.

- Deleting any cross-references in the specification to the earlier PCT specification to avoid including a description of (B) the locking mechanism by simple referencing.

- With no mention of (B) the locking mechanism in this divisional specification, this divisional application in principle would not be vulnerable to a possible future challenge to entitlement by Noel.

Step 2

Next, begin negotiations with Noel for an assignment of his IP rights, agree to co-ownership, or any arrangement that is commercially useful to SolVector.

If negotiations are successful, amend the parent Australian patent application as needed.

Otherwise, allow the parent Australian patent application to lapse and proceed with just the divisional application.

Steps 1 and 2 are not a completely perfect solution. If negotiations fail and if IP Australia concludes that Noel is an inventor and directs that Noel be recorded in the patent register as such, SolVector will have to develop a strategy in relation to the parent Australian patent application, and this time with Noel’s approval. That can get messy.

However, Steps 1 and 2 give SolVector the most bargaining power and control, especially in relation to invention (A) of the divisional application.

How does the tale end?

So, what happened in this very authentically real case?

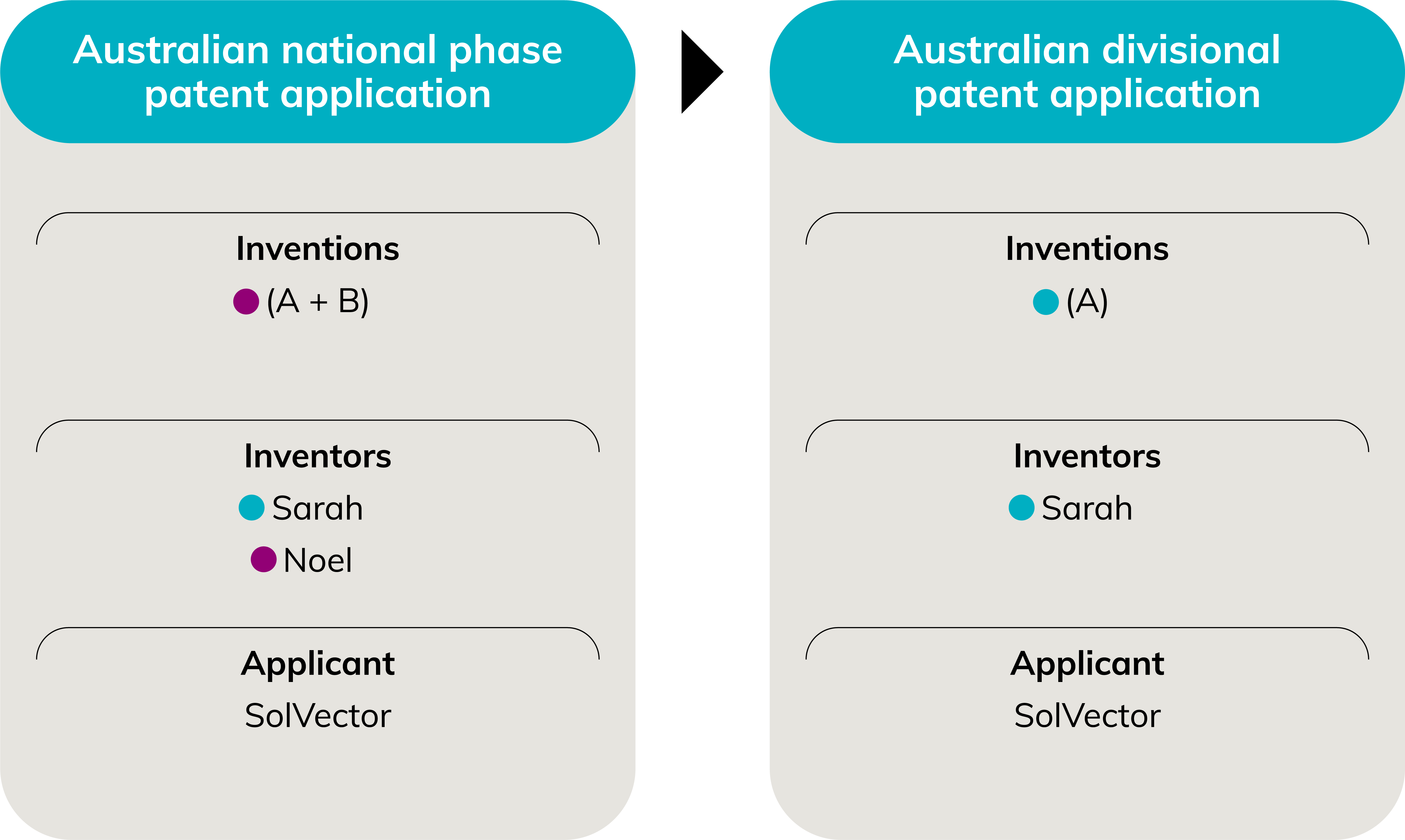

The divisional application, covering just (A) the motor system proceeded to acceptance with no entitlement issues. There were also no double patenting issues as the parent Australian patent application was not granted.

With the divisional application secured for SolVector, and after several rounds of negotiation, Noel agreed that in exchange for being named inventor on the parent Australian patent application and a single payment, he assigned all of his inventor rights to SolVector.

SolVector went on to delete claims to (A) from the parent Australian patent application and let both applications proceed to grant. SolVector’s leadership decided the extra renewal fees of two patents were justified (rather than one set) as it assisted the marketing-spin on the technical brilliance of their product. It also meant that SolVector could sell or licence inventions (A) and (B) separately in future if needed.

From cautionary tale to strategy

Content described in a specification can create inventors invertedly, even if the content is not part of a claim. Know the inventor of all the content included in a specification to avoid this issue.

- Inventorship is judged differently in different parts of the world. In Australia, an applicant must derive title from all inventors of the invention as described in the specification even if not the subject of any claim.

- Third party contributions must be managed proactively - interns, technicians, and consultants may be inventors. Written IP ownership agreements with third parties are always recommended.