Pharma Frontier series | The intersection of pharmaceutical patent litigation and the ACCC in Australia

Recent legal and regulatory developments are reshaping pharmaceutical patent settlements in Australia. We examine how competition law, market entry timing, and litigation strategy converge in this evolving landscape. This article is the first in our three-part Pharma Frontiers series on the intersection of IP and competition in the pharmaceutical sector.

Prior to President Trump’s so-called “Liberation Day”, concerns had been expressed by the US pharma sector about the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). According to lobbying efforts, the PBS was described as “egregious and discriminatory” towards the US pharma sector. The allegation was made to support the imposition of tariffs on imported Australian pharmaceuticals.

When the tariffs were revealed on Liberation Day, Australian pharmaceuticals were exempted. Whilst this may be the end of the US pharma sector’s attack on the PBS, the US pharma sector and indeed all global pharmaceutical business face three real challenges that are quite unrelated to tariffs and international trade generally. Rather, they are patent-related, with two of these challenges highlighting the intersecting nature of patents and the PBS.

In this article, we discuss the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) ability to regulate the Australian pharmaceutical industry through reviewing settlement agreements between competing parties in patent litigation.

In subsequent articles, we will discuss:

- The ability of the Australian Federal Government to recover damages incurred when a patent for a PBS listed product is invalidated.

- The requirement that all Australian patents must disclose the best method of performing an invention, not just patents pertaining to pharmaceuticals.

Regulatory change: The Repeal of section 51(3)

Background and impact on patent holders

The Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) was enacted to, amongst other things, regulate competition in the Australian market.

Prior to 13 September 2019, subsection 51(3) of the CCA provided a limited exemption for certain types of conduct, which otherwise would have been prohibited, if that conduct related to the exercise of intellectual property rights. Relevantly, for a patent right, imposing or giving effect to a condition of a licence or assignment for a patent right, to the extent that the condition related to the subject matter of that patent right, were exempt.

Impact of its repeal

In its September 2016 report, the Productivity Commission “Intellectual property arrangements-inquiry” found that intellectual property rights and competition law are not in fundamental conflict. Therefore, there was no rational basis for the exemption created by subsection 51(3).

ACCC scrutiny of Pay-for-Delay settlements

In its report, the Productivity Commission noted that in the pharmaceutical industry, there existed a strategy known as “Pay-for delay… whereby patent holders pay generic manufacturers, as part of a settlement for a patent infringement case, to keep their products off the market beyond the scope of a patent. Delays of this kind limit competition by restricting the number of products on the market and any subsequent price reductions, including those triggered under the PBS”.

It was recommended by the Productivity Commission that “A transparent reporting and monitoring system should be put in place to detect pay-for-delay settlements. This would require reporting to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) settlement arrangements between originator and follower pharmaceutical companies that affect the timing of market entry for a generic version of a product into the Australian market.”

Post-repeal regulatory framework

Impact of repealing subsection 51(3)

Once subsection 51(3) was repealed, conduct involving intellectual property rights became subject to the full anti-competitive conduct prohibitions in Part IV of the CCA in the same manner as all other conduct. This set the scene for the ACCC to not only take action against pay-for-delay arrangements but more broadly, cartel conduct; making or giving effect to a contract, arrangement, or understanding, or engaging in a concerted practice, for the purpose, or with the effect or likely effect, of substantially lessening competition; and engaging in exclusive dealing for the purpose, or with the effect or likely effect, of substantially lessening competition.

ACCC monitoring

Although the Productivity Commission recommended the adoption of a monitoring process, no such process exists. However, since patent litigation is conducted in the public domain, the ACCC would obviously be aware of any settlements arising out of the litigation and could act as it saw fit.

But what if parties enter an arrangement in the absence of triggering litigation? A monitoring process would require the detection of such an arrangement by the ACCC. By contrast, a notification process would require parties to provide details of the arrangement to the ACCC for assessment and approval. Such a notification process does not exist.

Instead of monitoring or notification, the ACCC has an authorisation process.

The ACCC authorisation process

Guidelines issued

In August 2019, the ACCC published “Guidelines on the Repeal of subsection 51(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010”. These guidelines provide a substantial overview of the approach that the ACCC will take in satisfying its statutory obligations for investigating and enforcing the anti-competitive conduct prohibitions of the CCA.

These guidelines remain current and can be found here: ACCC Guidelines - Repeal of Subsection 51(3)

Unfortunately, the examples provided in the context of the pharmaceutical industry, are not particularly helpful, except for the ACCC's assessment in example 5:

“Whether the ACCC would grant authorisation will depend on whether the conduct results in a net public benefit”.

Authorisation as legal protection

This may be used where businesses are concerned that proposed conduct would or might contravene the anti-competitive conduct prohibitions of the CCA. By seeking authorisation for this conduct, the parties receive statutory protection from legal action under the CCA for that conduct.

If the ACCC is satisfied that the proposed conduct is likely to result in a net public benefit, an authorisation may be granted. “Net public benefit” means the proposed conduct results in the public benefit outweighing any public detriment.

Without such an authorisation, parties entering into a settlement agreement would be exposed to an action by the ACCC for possible contravention of the CCA.

Because authorisation is a public process, the application, supporting submission along with interested party submission and comments, the ACCC’s draft and final determination are published.

Competition in the Australian pharmaceutical market

Revenue comparison

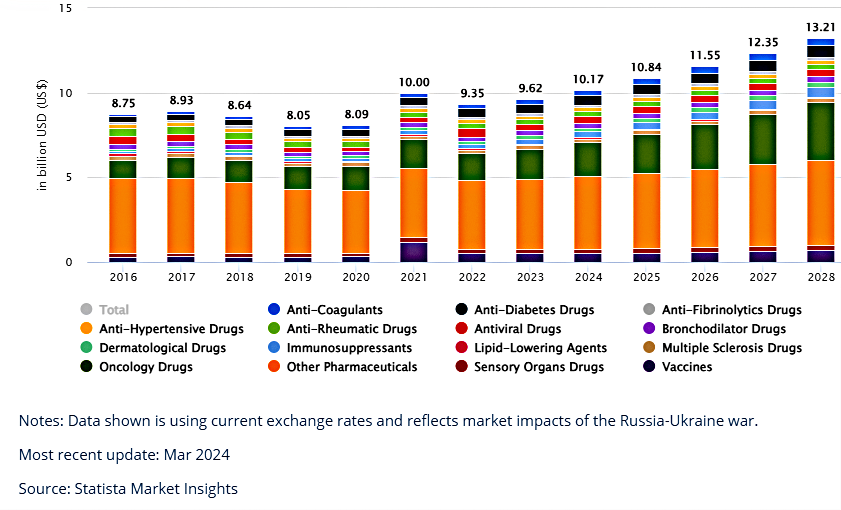

The following data illustrates changes in revenue (USD) by product category from 2016 to 2023, with projections to 2028. It is suggested that growth from 2023 will be about 6.76% per annum.

Looking at the projected 2024 revenue of 10.16bn USD for the Australian market, the US market by comparison is projected to be about 60 times that of Australia at 636.9bn.

Does this gross difference in market size mean that Australia is so unattractive that few pharmaceutical companies have an interest in the market? This would appear not to be the case primarily because of the PBS.

This scheme aims to provide affordable medicines to all citizens at a subsidised price. Since the PBS covers both generic and patented originator medicines, the subsidies paid to pharmaceutical companies will vary from relatively low amounts for highly competitive generic medicines to substantial amounts for example, for orphan drug medicines.

A 2024 example of the price difference between PBS and non-PBS medicines, for, PAXLOVID®, a patented medicine for the treatment of Covid 19, is as follows:

Private prescription price: $1,159.50.

PBS price: $30.60

With a price difference of $1,130, it is highly likely that sales of a medicine that is PBS listed will be somewhat higher than if the medicine is not listed. Hence the attractiveness of a PBS listing and the overall attractiveness of Australia for pharmaceutical suppliers.

Competition and Market Structure

Since PAXLOVID® is a patented medicine, competition will only arise for alternative medicines having comparable therapeutic activity.

By contrast, generic medicines will be subject to competition from other identical generic medicines as well as alternative medicines having comparable therapeutic activity. In this sense, this part of the market is somewhat more like the market in Australia generally for non-patented goods. With the exception that, generic medicines are also PBS listed. For this reason, the Australian generic market is still attractive to pharmaceutical suppliers.

PBS pricing and market dynamics

Pricing structure under the PBS

In recognition of the exclusive nature of a patented medicine, the amount paid by the Federal Government for such medicines will be somewhat higher than for a generic medicine. Under the PBS, all medicines are listed under either an F1 formulary (patented, single brand medicines) or an F2 formulary (generic medicines).

Importantly, when a medicine becomes generic, the price paid under the PBS to the originator is generally reduced by 25%.

Clearly a medicine may become generic because relevant patent(s) have either expired or been found invalid. In any event, information about the size of the market for an F1 medicine will become evident to a generic supplier. Such a supplier will be able to assess the risk of challenging patent validity versus market opportunity.

Licensing and PBS listing

Whilst the outcome for the generic is quite clear when either patent validity or invalidity is Court determined, is it permissible to enter into a licence with the patent owner as a means of settling litigation and allowing the generic to enter the market, especially by seeking PBS listing?

The Federal Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for administering the PBS. In a 1 July 2022 policy statement on PBS listing of an FNB (first new brand, i.e. generic), the Department advised:

“The existence or status of a patent relating to a drug, or the existence of a dispute (including litigation) over the validity or infringement of a patent, is not a matter that the Department considers when processing an application for the listing of an FNB.”

This makes quite clear that the existence of any patent litigation relevant to a generic listing will not impede the PBS evaluation of that listing.

Settling litigation and ACCC authorisation

Acceptable settlements

Whilst clearly “a pay-for-delay” type settlement would not be authorised, what would constitute an acceptable settlement? Given the statutory benefit of gaining authorisation, it is to be expected that the litigants would be more likely to engage with the ACCC.

Case study: Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd and Natco Pharma Ltd v Celgene Corporation [2021] FCA 236

The first and so far, the only parties to avail themselves of the ACCC authorisation process, were the generic suppliers Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd and Natco Pharma Ltd on the one hand and on the other hand, the originator, Celgene Corporation.

The focus of this interlocutory litigation was the Celgene product REVLIMID®, a PBS listed medicine.

One of the observations made by Beach J supports the contention of the economic importance of obtaining PBS listing:

97. Now it is not commercially viable to supply a pharmaceutical product in Australia unless that product is listed on the PBS.

Motivations for settlement

In any patent infringement litigation, there is always the risk that a patent will be found invalid. For the pharmaceutical industry, this may have quite significant global implications. It would provide motivation for generic suppliers to challenge validity in other jurisdictions. Since it is relatively difficult to prove patent invalidity in Australia, a successful patent challenge in Australia would provide further motivation to challenge in other jurisdictions.

Accordingly, it is possible that Celgene would have been amenable to settling any litigation around its patent to avoid a finding of invalidity.

Equally, Juno and Natco would be mindful of the possibility that the patent would be found valid.

Therefore, settling the litigation on a commercially favourable compromise would have seemed attractive to the parties.

To avoid ACCC scrutiny and the possible highly negative consequences, the parties decided to reach an agreement and to seek ACCC authorisation for their agreement.

The ACCC authorisation process

Since the ACCC acts in the public interest, all documents, except those which are confidential, are available at: ACCC authorisation register - Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd & Ors

Authorisation request

On 3 December 2021, the ACCC received an application for authorisation from Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (Juno), Natco Pharma Ltd (Natco), Celgene Corporation and Celgene Pty Ltd (together, Celgene) (altogether, the Applicants).

The Applicants sought authorisation to enter into, and give effect to, certain operative provisions of a settlement and licence agreement that would enable Juno and Natco to bring to market generic versions of Revlimid® and Pomalyst® from a specified launch date for each drug. The Applicants sought authorisation until 2 August 2027, when the last of the relevant Celgene patents is due to expire.

The Applicants sought authorisation to settle a patent dispute before the Federal Court of Australia.

ACCC’s initial response and market feedback

On 15 December 2021, the ACCC sought submissions from interested parties disclosing certain aspects of the parties proposed Agreement:

- Non-exclusive, non-sublicensable, non-transferable licence to Juno and Natco

- Natco permitted to seek PBS listing, provided the listing is not effective until the Authorised Launch Date

- Juno and Natco will not manufacture, import or distribute relevant generic products until the Authorised Launch Date

- Juno and Natco will not export relevant generic products

- Juno will not assign or transfer any relevant ARTG registration without Celgene’s approval, unless it is to Natco

- Juno and Natco will not participate in any invalidity proceedings against Celgene’s relevant patents

- Celgene will not institute any proceedings against Juno and Natco, including distributors and wholesalers in respect of relevant generic products after the Authorised Launch Date

- Juno and Natco will not exercise any right of appeal arising from the Federal court proceedings

- The parties release each other unconditionally from all Australian proceedings relevant to Celgene’s patents and the relevant generic products

Submissions made to the ACCC, may be summarised as follows:

Support for authorisation

- Generic entry will trigger an immediate 25% reduction in price to the PBS.

- Further price reductions may occur because of the PBS mandatory price disclosure process.

- Non-PBS price benefits

- Increasing indications

Against Authorisation

- Celgene obtains a PBS price premium

- Potential decreased use of PBS listed products

- Originator product withdrawn from the market

The ACCC also sought detailed responses from the parties to the agreement (letter 16 December 2021). More details in the ACCC's request for information are available at: ACCC to Celgene - Request for information (PDF)

This request was largely in response to the parties to the agreement contention that the proposed conduct would give rise to a public benefit in the form of:

- cost savings to the Australian Government

- greater supply security

- litigation cost savings.

Draft determination and outcome

ACCC's draft decision - Authorisation denied

On 23 March 2022, the ACCC published a draft determination which proposed that authorisation be denied: Draft determination summary - 23 March 2022 (PDF)

In summary, the ACCC was not satisfied that the claimed public benefits would arise over any public detriment. Specifically:

- The 25% cost saving the PBS was unquantified and, in any event, if the Celgene patents were subsequently found invalid, the Federal Government could recover some of its costs expended under the PBS.

- No supply issues were identified.

- The ACCC was not satisfied that the litigation would proceed without the proposed conduct.

As a result of the negative draft determination, further submissions were made by the parties to the agreement. Unfortunately, these are heavily redacted, the ACCC noting in its draft determination:

The Applicants provided very few internal documents and have claimed confidentiality over much of the information provided to the ACCC to date.

No ACCC final determination

An ACCC final determination was due on 29 July 2022. However, on that day, the application for authorisation was withdrawn by the parties. Consequently, we cannot know if the ACCC would have reversed its position expressed in the draft determination. But given the strength of the draft, this seems unlikely.

Commonwealth of Australia - recovery of PBS costs

This was one of the ACCC’s reason for declining authorisation and will be covered in a subsequent article.

Conclusion

A generic party will usually be an infringer of a pharmaceutical compound/composition patent. Therefore, in assessing the risk of pursuing a product launch, a generic party must determine the strength of its invalidity case realising that it may be committing to funding an appeal to the Full Federal Court. Clearer guidance from the ACCC on acceptable settlements would allow a generic party to better assess the commercial implications of commencing litigation.

Of course, an originator would also be in a more favourable position if the ACCC authorisation criteria were known. For example, the balancing of the costs of defending its patent versus revenue foregone in providing a licence to a generic party. A patent defence strategy would always include a review of claim scope to determine desirability of patent amendments before the Australian Patent Office and if a patent term extension was granted, a reassessment of the validity of the extension.

For now, faced with a seemingly high barrier to obtain authorisation, both generic parties and originators need to be fully prepared to litigate each matter to completion.