Protein modelling to support IP strategies

Written by Ken Seidenman (FB Rice) and Simona John Von Freyend (PTNG Scientific)

This article was first published in Australasian Journal of BioTechnology, October 2025, Volume 25, No 2

Protein modelling is an increasingly powerful discipline in the pursuit of defensive and offensive IP strategies in the commercialisation of protein therapeutics.

Over the past few years, computing power and developments in protein modelling have begun to offer unprecedented opportunities to explore the tolerance of antibodies or other proteins of commercial interest to mutations in functional domain sequences.

These in silico methods can aid in the design of libraries of variant sequences that, with increasingly higher hit rates, not only retain original function, but, in some cases, actually improve functional properties of the starting protein or antibody (e.g., binding affinity or target selectivity) despite multiple amino acid substitutions.

In this article, we look at a (de-identified) case study to illustrate the power and commercial implications of these approaches in both defensive intellectual property strategies; for example, designing around a patent claim to an antibody of interest, and offensive intellectual properties to obtain in silico-supported claims around a potentially broader ‘genus’ of protein sequences.

The latter approach renders design round of such claims using the same in silico approaches more challenging to potential commercial competitors.

Protein modelling: the beginnings of a sea change

In 2018, DeepMind’s AlphaFold algorithm burst onto the protein structural modelling scene and blew all other predictive tools out of the water with a less than 90 per cent accuracy of the true molecular structure. This level of accuracy is comparable to the atomic level of detail found in traditional crystal structures.

AlphaFold (and its increasingly improved incarnations), with the rapidly growing computing power readily available today, offers unprecedented opportunities to accelerate early-stage therapeutics development. It is now possible to use computational structure predictions to design new protein functions, enhance binding affinities, and even design completely de novo proteins, including enzymes.

The state of play for protein modelling: a potential challenge for patent protection of protein therapeutics

Travellers on the long protein therapeutic commercialisation journey are well aware of the importance of obtaining patent claims that provide an effective commercial barrier to would-be competitors. In large part, the effectiveness of protein and antibody claims in blocking potential competitors depends on the scope of such claims. In some patent jurisdictions, such as the United States and Australia, the standards, particularly for antibody claims, are very strict and typically require that the scope of a claim to an antibody against a target of interest be limited to antibodies that have the exact same amino acid sequence for all six CDRs. In other words, if a competitor to the patentee develops an antibody that binds to the same target of interest but differs by one or two amino acids in any of the six CDRs, the competitor’s antibody would not be covered by the above-mentioned CDR-limited antibody claim.

It will be quickly appreciated that the protein modelling approaches now available will drive a progressively rapid and affordable path to ‘designing around’ protein and antibody patent claims, as computational approaches prove increasingly accurate at predicting amino acid substitutions in a claimed protein to yield (e.g., antibodies that have similar or better binding affinity). We emphasise that this is not merely a hypothetical scenario, as demonstrated by the following de-identified anecdote.

An antibody, a patent claim and a protein modeller

One of us (Simona) and the team at PTNG Scientific worked with a small biotechnology company interested in using an antibody for a promising, novel indication; however, the antibody was protected by an existing patent and the client concluded that generating an antibody variant with one amino acid substitution in each of the CDRs would work around the existing patent protection.

Brute force experimental trial and error testing to identify the relative handful of variants of the claimed antibody that would retain antigen binding despite six CDR mutations was daunting, as there are 64 million possible sequence variations. However, with the help of structural biology and in silico modelling, PTNG narrowed down the candidate set, aiming for functional equivalence, but with enough sequence variation to fall outside of the relevant claims.

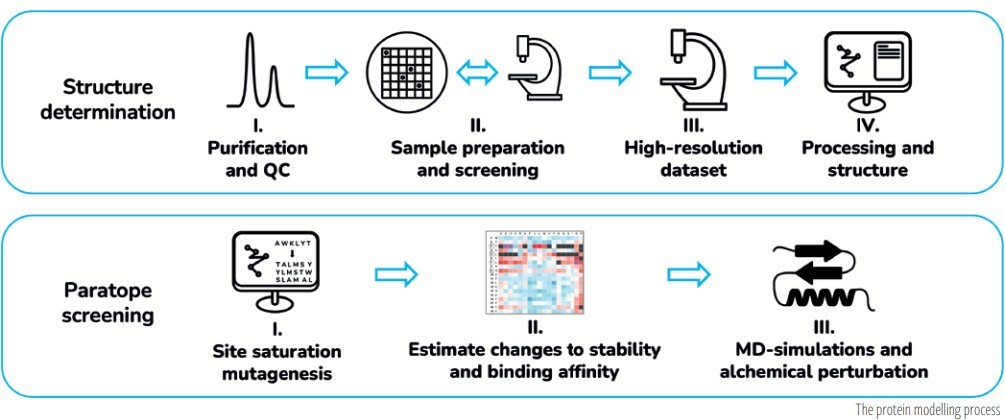

In brief, the modelling process (summarised in the accompanying diagram) utilised virtual saturation mutagenesis across all CDR positions in the antibody of interest. Molecular dynamics simulations were then run to assess the impact of each mutation or sets of mutations on the interaction of the CDRs with the target antigen. Perturbation simulations were then applied to double-check binding free energy calculations and further validate tolerated substitution predictions. Only those structures predicted to be stable (via energy scores of the bound complex), and having high affinity to the antigen were then progressed. The biotech company went on to validate, experimentally, the predicted sequences and were able to move forward with the commercial development of their variant antibody, which was not covered by the patent claims for the starting antibody.

Playing offense: design-around proofing in silico

As the above example illustrates, we believe that it will become increasingly important for innovators seeking robust patent coverage of new protein therapeutics (e.g., an antibody to a new therapeutic target) to exploit protein modelling approaches to allow for broader protein/antibody patent claim coverage, particularly in jurisdictions such as the United States that are very strict on allowable sequence variations. The rationale for this view is at least threefold. First, the use of protein modelling to rapidly identify, in silico, will afford the generation of a plausible subset of protein sequence variants to be identified that can be validated experimentally within tractable timelines and budgets, and then incorporated into patent specifications and claims.

Second, although it will often not be possible to experimentally test all candidate sequence variants, as the predictive accuracy of protein modelling approaches increases, the patentee incorporating predicted functional sequences into patent claims will be in an increasingly strong position to argue to generally sceptical patent examiners that such claims are justified even when not every single sequence has been experimentally tested.

Third, even in the case where a patentee is unable to obtain claims encompassing in silico–only sequence variants, the publication of a patent application with such lists of sequences will serve as prior art against patent claims covering sequence variations advanced by potential competitors, which serves as a disincentive to competitors entering that commercial space.

We believe that it will become increasingly important to commercial players interested in developing protein and antibody-based products to reckon with the state-of-the-art in computational modelling by integrating modelling approaches strategically both ‘offensively’ starting from the research that identifies a protein/antibody with commercial potential to maximise potential patent protection by in silico expansion of sequence possibilities, and ‘defensively’ by using computational tools to design around patent coverage.

The most important point is for all actors in the space to be very aware of the

potential commercial implications of protein modelling we have outlined here and plan accordingly. In the words of Wayne Gretzky, ‘Skate to where the puck is going, not where it has been.’

The views expressed in this article reflect the co-authors’ opinions and must not be relied on in lieu of advice from a qualified professional in respect of your particular circumstances. To the maximum extent permitted by law, FB Rice does not make, and excludes, any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of any information in this article and FB Rice (collectively, with its partners, officers, directors, employees, agents and advisers) expressly disclaims any and all liability for any loss or damage, howsoever caused, relating to these materials or from acting in reliance on the information within it.