Importing Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Challenge or Opportunity?

Explore the critical factors in importing Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) into Australia, including the extraterritorial reach of Australian patents, the implications of overseas manufacturing, and insights from the UK and US. This third article in our ADC series also offers strategic insights to help innovators navigate the complexities of the global market.

Innovation in the field of ADCs is continuing to accelerate, with no sign of slowing down. Widely regarded as the next generation of breakthrough medicines, ADCs offer the potential for highly targeted therapies in a broad array of diseases, and particularly cancers.

The Evolving ADC Landscape: Growth and Market Shifts

The rapid pace of innovation is best evidenced by a clinical pipeline that, as at 2024, included over 180 ADCs in various stages of development.1 To boost in-house ADC clinical pipelines, there has been a recent flurry of mergers and acquisitions – most notably, Pfizer’s doubling of its oncology portfolio through the $43 billion acquisition of Seagen’s ADC programs in 2024. More recently, 2025 has commenced with some significant, and costly, challenges for the field, as pharmaceutical companies look to focus and invest heavily in the most promising ADCs and trim funding for otherwise underperforming ADCs. For example, Pfizer has only recently announced the axing of its B7H4V ADC, concluding that the molecule is unable to “achieve a meaningful impact over standard-of-care chemotherapy” in the highly competitive B7-H4 space.2 Genmab also discontinued its B7-H4 program in November 2024.3

Navigating Patent Complexities in ADC Development

To realise the true value of ADCs, innovation must be protected. As discussed in our recent article, patent filings in the ADC field are growing exponentially, with new filings encompassing not only the ADC itself, but also novel formulations, dosing regimens, chemical syntheses and manufacturing methods, combination therapies, and methods of treatment. Understanding this growing and dynamic patent landscape provides crucial insights for innovators, shaping both IP and commercialisation strategies for ADC therapies.

ADCs comprise individual components that are eventually linked together to form the conjugate. In its simplest form, these components include the antibody, the drug, and the linker. Current innovation in ADCs is driven not only by the development of individual components, such as new drugs or isolated antibodies, but also by the specific combination of these components. For example, the complimentary and optimised pairing of a therapeutically active drug with a highly specific, targeting antibody.

As a result, assessing freedom-to-operate and potential patent infringement for ADCs involves unique considerations. As discussed in our earlier article, the freedom-to-operate of each component must be evaluated. For example, does the drug component remain protected by existing patents, posing an infringement risk if conjugated to an antibody? Similarly, the antibody component must be assessed for patent protection that could prevent its use in an ADC. Even further, the linker must be examined for patent protection, whether alone, conjugated to either of the drug or antibody, or used in the entire ADC.

It is therefore clear that assessing freedom-to-operate, and the risk of patent infringement of an ADC can be a particularly complex, especially in view that Australian patents can have extraterritorial reach.

Extraterritorial reach of Australian patents

The Patents Act defines ‘exploit’ as, where the invention is a product, the make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things.4 The term ‘exploit’ is broad and encompasses a wide range of commercial uses, presenting a significant infringement risk.

Where an antibody or drug component is protected by granted composition of matter claims, its use in an ADC application will be considered exploitation, and therefore an infringement of those granted composition of matter clams. Similarly, importation of the antibody or drug component is an infringement of those granted composition of matter claims. Ultimately, importing a drug or antibody component of an ADC that is protected by granted composition of matter claims in Australia is an infringement.

From a practical perspective, it is typical that granted composition of matter claims are the first to reach lifetime expiry. In contrast, follow-on granted process claims may remain in force for several further years. For an ADC innovator, it is often the case that these follow-on process claims are a final freedom-to-operate hurdle to clear.

An obvious work-around to avoid infringement of these granted process claims is to import the “ready-made” drug or antibody component. The rationale being that, as the component is not synthesised or manufactured in Australia, it will not infringe any such granted process claims.

However, beware, as this is not the case, and there remains an infringement risk.

Importation into Australia of a product manufactured overseas using a patented process or method constitutes infringement.5 That is, the extraterritorial reach sees that the importation of a product synthesised by a patented process will infringe granted claims protecting that process if it can be established that the product was manufactured overseas according to that process.

Therefore, importation of any component of an ADC into Australia will constitute infringement of a granted Australian process patent that results in production of that component.

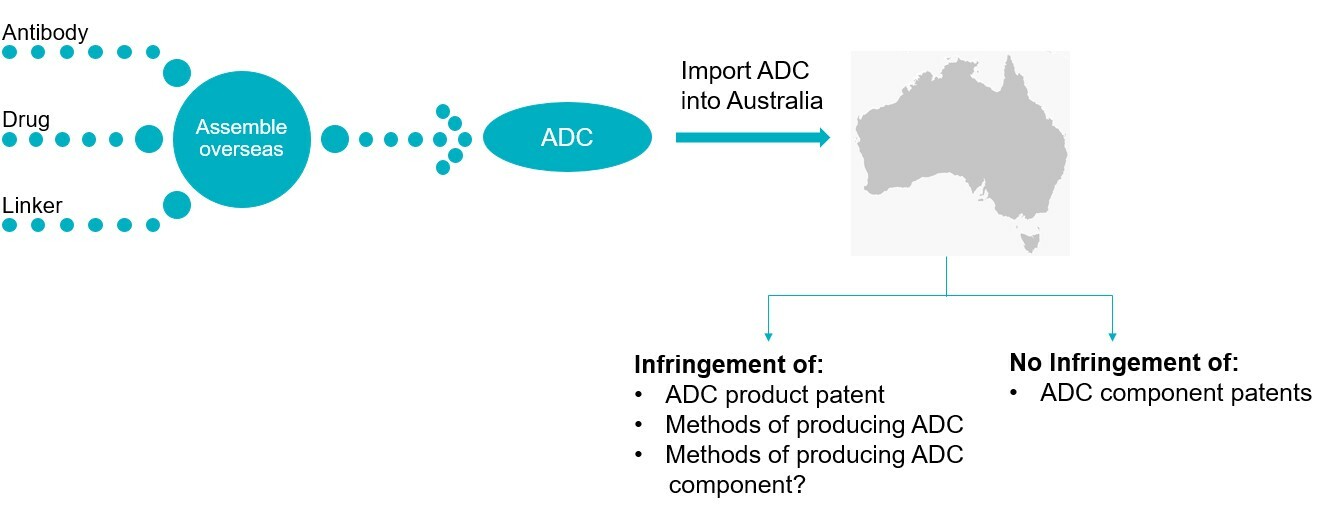

What if your ADC is assembled overseas prior to importation into Australia?

According to the Saccharin doctrine, importation of a non-infringing product may still constitute infringement of granted process claims, if that process was used in the manufacture of the product overseas. For example, importation of an ADC in its entirety may infringe granted process claims directed to manufacturing a single component, if that single component was manufactured by the patented process overseas.

However, importation of an ADC into Australia will not constitute infringement of a granted product claim covering an ADC component even if it can be established that the component was used outside of Australia to manufacture the ADC that is subsequently imported into Australia.6

Ultimately, even if an ADC is itself not protected by granted product claims, its importation still introduces additional complexities for ADC innovators when evaluating freedom-to-operate and infringement risks.

The United Kingdom and United States perspective

Similar to Australia, the importation of a product arising from a patented process encounters complex issues in both the UK and the US. Even if a product has been modified slightly prior to importation, the UK and US courts have considered this to be an infringement of granted process claims if the modifications do not result in a "loss of identity"7 or have not “materially changed”8 the product of the patented process.

To mitigate patent infringement risk, ADC innovators conduct thorough freedom-to-operate analyses in all jurisdictions of interest.

Strategic considerations for ADC innovators

When an ADC innovator is considering its freedom-to-operate position and risk of infringement, it is essential to understand the extraterritorial scope afforded to patent claims, particularly process claims.

While importation into Australia of either i) individual ADC components, such as the drug or antibody, or 2) the complete ADC, may appear to be a work-around to avoid infringement risks, the extraterritorial reach of process claims requires further consideration.

As it stands, infringement proceedings relating specifically to ADCs are yet to make their way to Australian courts. However, with innovation in the ADC field continuing to accelerate, it remains only a matter of time until we learn the true implications of importation on freedom-to-operate and risk of infringement of third-party rights.

Work with experienced IP counsel to maximise your ADC portfolio’s value. Contact our team for guidance on IP strategy, regulations, and global markets.

Footnotes

Pfizer axes B7-H4 ADC, triggering $1B impairment charge as blockbuster vision evaporates, Nick Paul Taylor, 4 February 2025; Fierce Biotech.

Genmab axes 3 programs to focus on plumped-up pivotal pipeline, Nick Paul Taylor, 7 November 2025; Fierce Biotech.

Schedule 1 of the Australian Patents Act 1990

Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008] FCA 559

Mylan Health Pty Ltd v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 28.

Medimmune v Novartis [2011] EWHC 1669

Amgen Inc. v. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., 580 F.3d 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2009).